It all began during my internship at the Ångström Advanced Battery Centre (ÅABC) in Sweden, where I took my first real step into the world of low-temperature electrolytes. What started as a simple curiosity why do batteries lose their power in the cold? quickly turned into a deeper exploration.

Later, I shared this journey in a YB3S seminar, offering an overview of what really happens when batteries meet the cold. The response convinced me that this topic deserves more attention not only from researchers, but from anyone interested in how energy technology faces nature’s extremes.

In this blog post, my goal is to open that door a little wider: to give you a broad yet insightful look into the field, touching on the key challenges, the main findings from the literature, and a few ideas for those who want to go further. I’ll keep it grounded in research, but also guided by curiosity with plenty of references for anyone eager to dig deeper.

So, let’s begin with the most fundamental question: why does temperature matter so much for a battery?

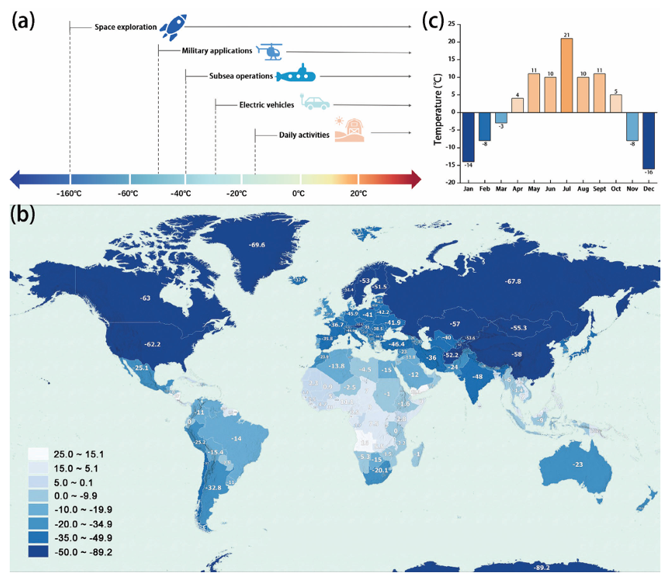

Most of the research so far, however, has focused on room-temperature operation. That’s where things work smoothly in the lab but not always in the real world. Many of our modern technologies demand reliable energy far beyond 25 °C: electric vehicles that must drive through Scandinavian winters, submarines operating under the Arctic Ocean, satellites orbiting at −100 °C, or military and rescue devices functioning in the coldest conditions on Earth. According to Yang et al. (Advanced Science, 2024), these applications can require batteries capable of functioning anywhere from 0 °C down to −160 °C a range that current systems struggle to handle.

The diversity of Earth’s climate further amplifies the challenge. As seen in temperature maps of 2023, vast regions from Canada to Siberia, Northern Europe, and Central Asia experience winter minima below −40 °C, while even temperate cities like Beijing record months of subzero daily temperatures. That means for nearly half the year, in much of the inhabited world, our batteries are operating outside their comfort zone.

temperatures in various countries/continents of the world. Resources from https://vividmaps.com/. Reproduced with permission. Copyright 2024,

Vivid Maps. c) The lowest monthly temperatures in Beijing in 2023. Data from China Weather Network. Figure taken from Yang et al. (Advanced Science, 2024).

Unfortunately, today’s lithium- and sodium-ion batteries still fall short under these conditions. Their internal resistance skyrockets, their capacity drops, and their electrodes and electrolytes lose harmony. Yet, the future of sustainable energy from electric mobility to space exploration depends on solving exactly this problem.

That’s why low-temperature battery research matters. It’s not just about chemistry; it’s about enabling human activity in every environment our planet (and beyond) presents.

What Goes Wrong at Low Temperatures?

When a battery is exposed to low temperatures, its entire electrochemical rhythm slows down. The overall reaction rate drops, internal resistance rises, and capacity begins to fade. Behind these symptoms lies one fundamental reason: the obstruction of ion transport.

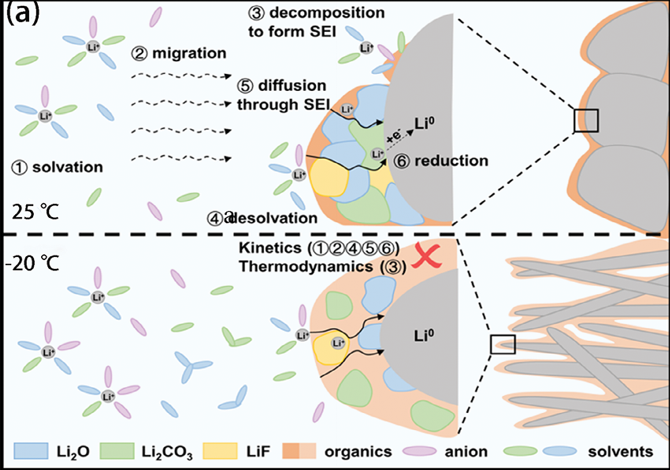

In a normal discharge process, ions are extracted from the cathode and travel across the cathode–electrolyte interphase (CEI). They then move through the bulk electrolyte as solvated species, shed their solvent shells at the solid–electrolyte interphase (SEI), pass through that SEI barrier, and finally intercalate into the anode. Each of these steps is temperature-dependent and at low temperature, each becomes a bottleneck.

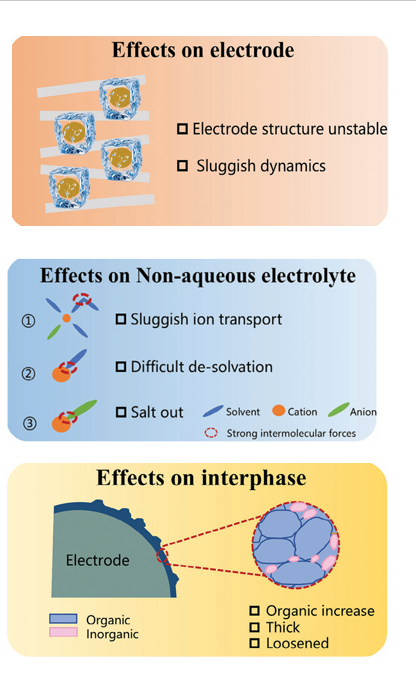

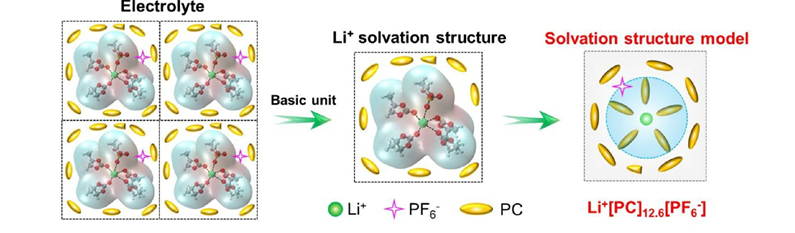

As Yang et al. (2024) describe, the viscosity of the electrolyte increases dramatically in the cold, thickening the medium through which ions must move. This leads to sluggish ionic transport and, at even lower temperatures, can cause salt precipitation or even freezing of the solvent. Meanwhile, the ions that do manage to move face another barrier: desolvation. The stronger solvent–ion interactions at subzero conditions make it harder for Li⁺ or Na⁺ to break free from their solvation shells, which disrupts the delicate balance between solid and liquid phases at the interface.

The electrodes are not immune either. Diffusion within the electrode particles slows, charge-transfer kinetics become sluggish, and lattice structures may experience stress or instability. The result is an increase in voltage hysteresis and a sharp decline in reversible capacity both hallmarks of poor low-temperature performance.

In short, low-temperature operation transforms the cell from a synchronized electrochemical system into a crowded highway, where every ion meets resistance at every stage. Understanding which of these stages diffusion, desolvation, or SEI transport becomes the main obstacle is crucial.

Low-Temperature Effects on the Electrolyte

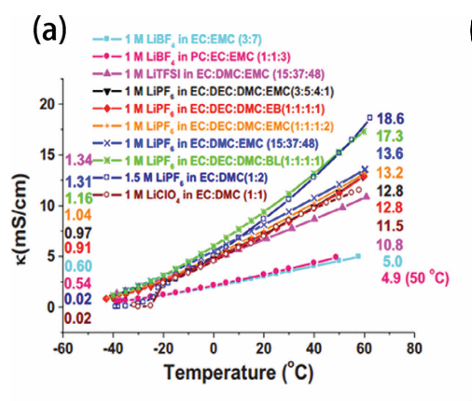

When a battery cools down, everything inside slows — starting with the electrolyte. The reduced thermal motion strengthens the bonds between solvent molecules, ions, and even the ions themselves. What used to be a fluid, fast-moving medium turns heavier and stickier.

This shift leads to a higher viscosity and a greater dielectric constant, which might sound harmless but actually makes ion movement more difficult. The ions start to form clusters and aggregates, like traffic jams on a frozen road. As a result, both the ionic conductivity and diffusion coefficients drop sharply.

and 60 °C for each solution are listed, respectively, on the left- and right-hand sides of the graphs. Reproduced with permission.(D. Yaakov, Y. Gofer, D. Aurbach, I. C. Halalay, J. Electrochem. Soc.

2010, 157, A1383.) Figure taken from Yang et al. (Advanced Science, 2024).

Finally, the solvation and desolvation processes where ions attach to and detach from solvent molecules become painfully slow. In essence, the electrolyte, once the most dynamic part of the battery, turns into its biggest bottleneck when the temperature falls.

Low-Temperature Effects on the Interface

At low temperatures, the interface between the electrode and the electrolyte becomes the true battlefield of a battery. Here, the ions must desolvate, pass through the SEI, and finally intercalate into the electrode. When the temperature drops, this whole process slows dramatically and desolvation becomes the rate-determining step.

Y.J.Li,Z.X.Wang,X.F.Wang,Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 4474.)

Because ions cannot easily cross the SEI, they start to accumulate on its surface, leading to capacity loss and uneven deposition. The SEI itself becomes thicker, richer in organic components, and structurally unstable. Yoo et al. (2022) showed that at −20 °C, the SEI on graphite becomes less inorganic and more porous, increasing the risk of dendrite formation and short-circuiting.

To achieve stable cycling, a thin, inorganic-rich SEI is essential — one that allows ions to pass easily while blocking unwanted reactions. Chemistries that form compact inorganic phases, like LiF or Li₂CO₃ (often aided by fluorinated additives), have proven especially effective in maintaining interface stability under cold conditions (Chekushkin et al., 2021; Keefe et al., 2019)

Low-Temperature Effects on the Electrodes

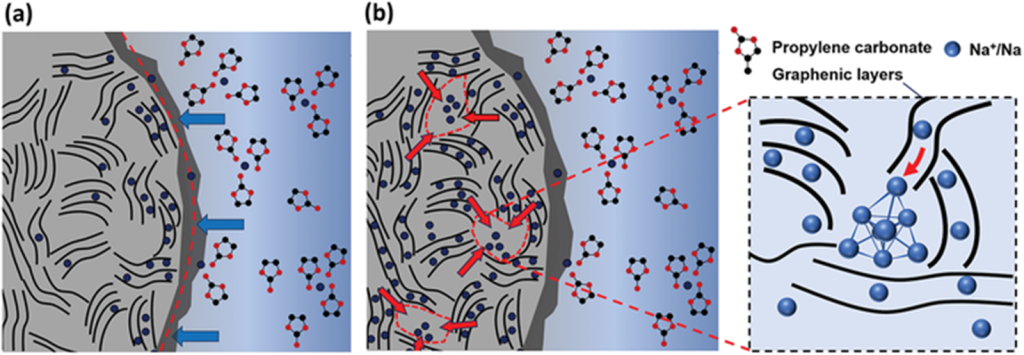

Inside the electrodes, the story is no different cold slows everything down. Ions that normally intercalate smoothly into the layered structure now move sluggishly, trapped between thermodynamic and kinetic barriers. As temperature drops, charge-transfer resistance (Rct) rises sharply and quickly becomes the dominant part of the cell’s impedance, especially around −20 °C.

Schematic illustration of how low temperature affects ion transport and structure within the electrode.

At subzero conditions, ion diffusion through graphenic layers slows, charge-transfer resistance increases, and morphological changes may induce side reactions. Structural design with shorter diffusion paths can alleviate these kinetic limits (adapted from Liu et al., Batteries, 2022).

The result? Greater voltage hysteresis, lower reversible capacity, and even structural stress within the electrode particles. In hard carbon or graphite, these stresses can lead to microcracks, exposing fresh surfaces that trigger unwanted side reactions or dendrite growth.

Improving low-temperature performance, therefore, isn’t just about electrolyte chemistry it’s also about engineering the electrodes themselves. Designing shorter diffusion paths and more open architectures can help ions find their way, even when everything else has slowed to a crawl.

Closing Reflections: Lessons from the Cold

Working on low-temperature batteries has shown me that cold isn’t simply an environmental condition it’s a microscope. It magnifies every hidden limitation in a cell: sluggish ion transport, unstable interfaces, and structural fatigue that would go unnoticed at room temperature.

But that’s also what makes this field so rewarding. Each frozen electrolyte or distorted impedance curve tells a story a piece of the puzzle that connects molecular chemistry to real performance. During my internship at the Ångström Advanced Battery Centre, I captured some of these moments on video: cells cooling down inside the fridge, impedance spectra shifting, and electrolytes crystallizing right before the camera lens. I’ll include a few of these clips below, offering a direct look at what “low-temperature behavior” truly means inside a battery.

This blog post also connects with my Young Battery 3S weekly seminar, where I presented these findings and discussed what really happens when batteries meet the cold. You can watch the full talk here: https://youtu.be/3wZOT741qsw?si=59D4L_mRMI345njW

There’s still a long way to go in understanding the complete picture from solvation kinetics and SEI evolution to electrode diffusion and structural design. Yet, every experiment adds clarity. Sodium-ion systems, in particular, represent an exciting frontier: abundant, affordable, and still full of mysteries waiting to be solved at low temperatures.

The cold exposes, but it also inspires. It slows everything down just enough for us to see to truly observe what’s happening inside. And in that stillness, new ideas begin to form…

For those who want to explore the science behind this post, here are the key papers that shaped this discussion.

References:

Yang, Y., Liu, M., et al. (2024). Challenges and Prospects of Low‐Temperature Rechargeable Batteries: Electrolytes. Advanced Science. Wiley-VCH. [DOI: 10.1002/advs.202410318]

→ Used in “Why Low-Temperature Batteries Matter” and “What Goes Wrong at Low Temperatures” to explain temperature ranges, real-world relevance, and ion-transport limitations.

Lutsenko, D. S., Belova, E. V., Zakharkin, M. V., Drozhzhin, O. A., & Antipov, E. V. (2023). Low‐Temperature Properties of the Sodium‐Ion Electrolytes Based on EC-DEC, EC-DMC, and EC-DME Binary Solvents. Chemistry, 5(3), 1588–1598. [https://doi.org/10.3390/chemistry5030109]

→ Cited in “Low-Temperature Effects on the Electrolyte” for conductivity loss and phase transition data.

Lei, S., Zeng, Z., Liu, M., Zhang, H., Cheng, S., & Xie, J. (2022). Balanced Solvation/De‐solvation of Electrolyte Facilitates Li-Ion Intercalation for Fast-Charging and Low-Temperature Batteries. Nano Energy, 98, 107265. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nanoen.2022.107265]

→ Used to explain solvation–desolvation kinetics and activation energy barriers in electrolytes.

Yoo, D. J., Liu, Q., Cohen, O., Kim, M., Persson, K. A., & Zhang, Z. (2022). Understanding the Role of SEI Layer in Low‐Temperature Performance of Lithium‐Ion Batteries. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.1c23934]

→ Referenced in “Low-Temperature Effects on the Interface” to describe SEI composition changes and dendrite risks.

Chekushkin, P. M., Merenkov, I. S., Smirnov, V. S., Kislenko, S. A., & Nikitina, V. A. (2021). The Physical Origin of the Activation Barrier in Li-Ion Intercalation Processes: The Overestimated Role of Desolvation. Electrochimica Acta, 372, 137843. [https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electacta.2021.137843]

→ Used alongside Yoo et al. in SEI discussion to highlight interfacial charge-transfer as a key barrier.

Keefe, A. S., Buteau, S., Hill, I. G., & Dahn, J. R. (2019). Temperature-Dependent EIS Studies Separating Charge Transfer Impedance from Contact Impedance in Li-Ion Symmetric Cells. Journal of The Electrochemical Society, 166(14), A3272–A3279. [https://doi.org/10.1149/2.0541914jes]

→ Referenced in the interface section for insights on temperature-dependent charge-transfer resistance.

Liu, B., Hector, A. L., Razmus, W. O., & Wills, R. G. A. (2022). Temperature Dependence of Hard Carbon Performance in Sodium Half-Cells with 1 M NaClO₄ in EC/DEC Electrolyte. Batteries, 8(9), 108. [https://doi.org/10.3390/batteries8090108]

→ Cited in “Low-Temperature Effects on the Electrodes” for electrode diffusion behavior and structural changes.

Li, Q., Lu, D., Zheng, J., Jiao, S., Luo, L., Wang, C. M., Xu, K., Zhang, J. G., & Xu, W. (2017). Li⁺ Desolvation Dictating Lithium-Ion Battery’s Low-Temperature Performance. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, 9, 42761–42768. [https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.7b13887]

→ Cited in “What Goes Wrong at Low Temperatures” and “Electrolyte Kinetics” sections for identification of desolvation as the rate-limiting step.

Mukai, K., et al. (2017). Superior Low-Temperature Power and Cycle Performances of Na-Ion Battery over Li-Ion Battery. Electrochimica Acta, 245, 1–10.

→ Referenced in “Low-Temperature Effects on the Electrodes” to support the Na-ion vs Li-ion comparison.

Ahmet Musab Beşbadem

Chemical Engineering Student, Gebze Technical University

Founder of musabbesbadem.com & Young Battery 3S

📧 ahmetmusabbesbadem@gmail.com | 🔋 YouTube: Young Battery Seeker